Photo by Insta360

Most riders treat onboard footage like a highlight reel. Something to post. Something to send to friends. Something to replay because the track day was memorable.

But here’s what most riders overlook:

Your onboard footage is one of the most powerful coaching tools you already own.

And here’s why:

- Even the best coaches can only see parts of your lap at a time.

- But your camera sees every corner.

- Every lap.

- And it never forgets.

Used correctly, your footage reveals:

- when your eyes move

- when your brake release begins

- how many steering inputs you use

- your apex timing

- your body position habits

- your line consistency

- your confidence (or tension) patterns

This guide shows you how to use it with purpose.

TrackDNA Safety Note

Riding motorcycles on track is inherently risky and can result in serious injury or death. The ideas in this article are shared for general information only — they’re not formal coaching, professional instruction, or a guarantee of safety or performance.

Always ride within your limits, use proper safety gear, and practice only in a controlled, closed-course environment that follows all rules and regulations. Before trying any new technique, talk with a qualified coach or instructor and use your own judgment about what’s right for your skill level, your bike, and your body.

The best place to explore and apply these ideas is with a qualified coach or at a dedicated motorcycle or racing school. Treat what you read here as background context and conversation fuel for your own training — not as a step-by-step guide or a substitute for in-person instruction.

By choosing to ride, you accept the risks that come with it.

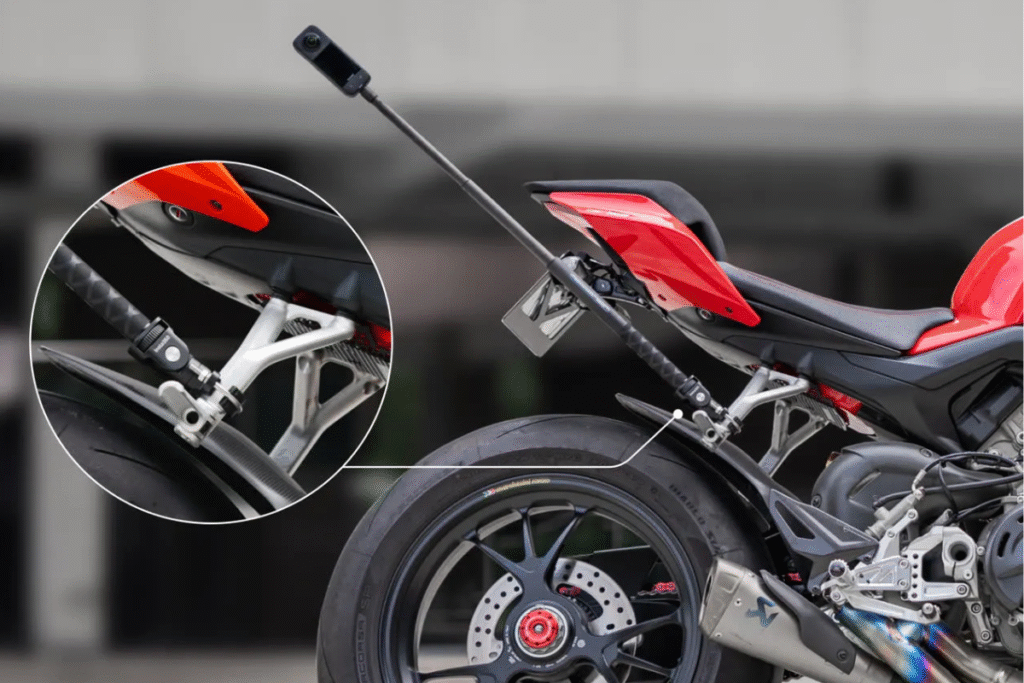

1. Choose the Right Camera Mount (and Follow Track Rules)

A good camera angle tells the truth.

A bad angle lies.

The most useful mounts are:

Chin Mount (Helmet)

Best for seeing:

- vision timing

- apex timing

- line of sight

- upper-body cues

Important: Some tracks—including COTA—do not allow chin-mounted cameras. Always check your track-day organization’s rules before mounting anything to your helmet or bike.

Chest Mount

Shows:

- head movement

- upper-body rotation

- shoulder tension

- consistency in body position

Tail or Rear-Facing Mount

Shows:

- lean angle visually

- rider stability

- line consistency

- mid-corner corrections

Fairing / Handlebar Mount

Shows:

- brake lever timing

- throttle timing

- steering inputs

This angle is extremely useful once you’re ready for deeper analysis.

A quick safety side note

Many organizations require safety wiring or tethering for any camera mounted to the bike or helmet.

This prevents the unit from becoming debris on track.

Always confirm your track rules — safety wires, tethers, or secondary retention straps are often mandatory.

2. Keep Your Recordings Short and Reviewable

Three-hour clips are useless.

The sweet spot is:

4–8 laps at a time.

Short clips let you:

- compare laps accurately

- spot repeat mistakes

- review without getting overwhelmed

- focus on learning instead of scrubbing footage

Quality > quantity.

3. What to Look for First (No Data Overlay Needed)

Before you add IMU/GPS overlays, look at the fundamentals.

A. Vision Timing

When we talk about “eye movement,” we are not referring to specialized eye-tracking devices.

We’re looking at:

- visible head movement

- when your visor turns toward the apex

- when your head leaves the apex and looks toward exit

If your head freezes, your vision is late.

B. Steering Inputs

Are you steering once?

Or adding lean mid-corner?

“Adding lean mid-corner” means:

You had to increase lean after the bike was already committed — usually due to:

- turning too early

- turning shallow

- hesitation

- late vision

- wide entry line

- rushed brake release

Your camera shows if this happens in the same spot every lap.

C. Body Tension

Video exposes:

- stiff shoulders

- locked arms

- unsupported core

- poor lower-body anchor

These often correlate with mid-corner instability.

D. Line Consistency

Are your lines repeatable?

Or does every lap look different?

Inconsistency reveals more than you think.

4. How to Self-Coach Without Overwhelm

Break your analysis down into single topics.

Example patterns to look for:

- “My eyes are late in T3, T4, T5.”

- “I steer twice on entry.”

- “I never get the bike fully stood up on exits.”

Onboard footage only works when you focus on one correction at a time.

A personal note for riders

I once asked a coach to film an entire 20-minute session while following me — and it became one of the most valuable tools I’ve ever used.

If you have a coach, a friend, or a riding buddy willing to film from behind or in front, that footage becomes a true educational resource.

Seeing your riding from another perspective exposes habits your own camera angle won’t always reveal.

Trade laps.

Trade cameras.

Use your network — it accelerates progress more than people realize.

5. What Onboard Footage Is NOT For

Avoid using your footage to:

- compare yourself to faster riders

- judge lean angle competitively

- critique your “style”

- obsess about aesthetics

The camera is for truth, not ego.

6. When Basic Footage Is Enough (and When You Need Data)

Basic footage shows:

- vision timing

- steering timing

- line choice

- posture

- tension patterns

- confidence patterns

Data overlays show:

- speed

- throttle timing

- brake application

- estimated lean angle

- acceleration zones

Most riders should start with basic footage first.

Once timing is consistent, data becomes meaningful.

7. How to Analyze Brake Timing

Footage shows:

A. When your lever begins to move

Late = rushed entry.

Early = wasted distance.

B. How you release the brake

Frame-by-frame comparison reveals:

- full brake

- brake taper

- release timing

- lean initiation

You want release leading into lean, not before it.

C. Smooth vs abrupt release

Abrupt release → front end unloads.

Smooth release → stable chassis.

8. How to Identify Steering Errors

Your footage shows:

- hesitation

- double steering

- shallow entry lines

- add-on lean corrections

Break down:

A. The moment your head leads

Head should rotate early.

Late head movement = late turn.

B. The number of steering inputs

One input = predictability.

Two or three = instability.

C. Your exit stand-up timing

Your footage shows exactly when you begin picking up the bike.

9. Reading Body Position From Footage

Look for:

Head Lead

Head should enter the corner before the torso.

Upper-Body Rotation

If your shoulders stay square, you increase lean demand.

Lower-Body Anchoring

If your knee, thigh, and outside leg aren’t stable, your arms compensate.

Tension Patterns

Shoulders, wrists, elbows — the camera doesn’t lie.

10. The Professional Analysis Method

This workflow is used by pro coaches and racers:

- Pick one corner

- Watch your most recent lap

- Watch your fastest lap

- Compare them side-by-side

- Look for differences in:

- vision

- brake release

- steering

- body position

- line

- Apply correction

- Re-record

- Verify the change

Professionals never guess — they measure.

11. How This Connects to Lean Angle

Your footage becomes the “mirror” for your lean-angle development.

It reveals:

- when the tire loads

- how smooth the brake release is

- whether steering is decisive

- how body position affects lean demand

- when the eyes leave the apex

- when roll-on begins

This is the practical, real-world application of the lean-angle framework you just learned.

12. The TrackDNA Footage Checklist

The 10 questions to ask of every corner:

- When do my eyes move?

- When do I begin braking?

- When does my brake release begin?

- Is the release smooth or abrupt?

- How many steering inputs did I use?

- Did my head lead the turn?

- Was my lower body stable?

- When did I begin rolling on?

- Is my line consistent?

- What changes between my slowest and fastest laps?

Closing — Your Camera Is Your First Coach

Onboard footage isn’t about showing off.

It’s about showing yourself the truth.

Used intentionally:

- your vision improves

- your lines stabilize

- your timing becomes predictable

- your lean angle becomes consistent

- your confidence grows

Your next lap begins with the last lap you reviewed.

Further Reading (Technique & Craft)

Author

-

Sean studied in Southeast Asia, did his stretch in corporate America as a Chief Revenue Officer, and then traded boardrooms for pit lanes. He’s a published author, and these days he’s on the grid with CMRA - on his way to MotoAmerica - and behind the scenes as the slightly obsessed human building TrackDNA, a magazine for riders who care as much about the culture and craft as they do about lap times.

Recent Posts